Financial fraud is a pervasive problem costing institutions and customers billions annually.1 Most known examples include credit card fraud, fraudulent online payments, and money laundering. Banks worldwide faced an estimated \(\$442\) billion in fraud-related losses in 2023 alone. In particular, credit card transactional fraud is projected to reach \(\$43\) billion in annual losses by 2026. Beyond direct losses, fraud undermines customer trust and damages banks’ reputation. For example, it leads to false positives where legitimate transactions are wrongly blocked. Consequently, financial fraud detection systems (a.k.a fraud scoring) must not only catch as much fraud as possible but also minimize false positives.

Fraudsters’ tactics evolve rapidly. Traditional rule-based systems (or simple statistical methods) have proven inadequate against today’s adaptive fraud models. On one hand, fraudsters form complex schemes and exploit networks of accounts. On the other hand, legitimate transaction volumes continue to grow due to the rise of e-commerce and digital payments.

This situation has driven a shift toward Machine Learning (ML) and AI-based approaches that can learn subtle patterns and adapt over time. Critically, financial fraud detection must happen in real-time (or near-real time) to intervene before fraudsters can complete illicit transactions. Catching fraud “closer to the time of fraud occurrence is key” so that suspicious transactions can be blocked or flagged immediately.2

This article deep dives into the current state-of-the-art of real-time transactional fraud detection, spanning both academic research and current industry practices.

I cover the major model families used today:

- Classical ML models: Logistic regression, decision trees, random forests, and SVMs.

- Deep Learning models: ANNs, CNNs, RNNs/LSTMs, autoencoders, and GANs.

- Graph-based models: GNNs and graph algorithms that leverage transaction relationships.

- Transformer-based and foundation models: Large pre-trained models like Stripe’s payments foundation model.

For each category, I discuss representative use cases or studies, highlight strengths and weaknesses, and comment on their suitability for real-time fraud detection.

Classical ML Models

Classical ML algorithms have long been used in fraud detection and remain strong baselines in both research and production systems.

These include linear models like logistic regression, distance-based classifiers like k-Nearest Neighbors, and tree-based models such as random forest and gradient boosted trees (e.g., XGBoost).

These approaches operate on hand-crafted features derived from transaction data (e.g., transaction_amount, location, device_id, time_of_day, etc.), often requiring substantial feature engineering by domain experts.

Logistic regression is a foundational model in fraud detection. Banks and financial institutions have historically relied on it due to its simplicity and interpretability (each coefficient \(w_i\) has a direct and intuitive meaning). A positive coefficient means the feature increases the log-odds of fraud, a negative coefficient means it decreases the risk.

\[P(y = 1 \mid \mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x} + b)}}\]- \(\mathbf{x}\): Feature vector (e.g., transaction amount, time of day, merchant category)

- \(\mathbf{w}\): Coefficients (risk factors)

- \(b\): Bias or intercept

Even today, logistic models serve as interpretable baseline detectors and are sometimes combined with a Business Rule Management Systems. However, linear models struggle to capture complex non-linear patterns in large transaction datasets.

Decision trees and ensemble forests address this by automatically learning non-linear splits and interactions. In fact, boosted decision tree ensembles (like XGBoost) became popular in fraud detection competitions and industry solutions due to their high accuracy on tabular data.3 These models can capture anomalous combinations of features in individual transactions effectively, learning complex, non-linear interactions between features. For example, the winning solutions of the IEEE-CIS fraud detection Kaggle challenge (2019) heavily used engineered features fed into gradient boosting models, achieving strong performance (AUC ≈ 0.91).

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have also been explored in academic studies. However, while they can model non-linear boundaries (with kernels), they tend to be computationally heavy for large datasets and offer no interpretable output. Therefore, the industry has gravitated more to tree ensembles for complex models.

Strengths

Classical ML models are typically fast to train and infer, and many (especially logistic regression and decision trees) are relatively easy to interpret. For instance, a logistic regression might directly quantify how much a mismatched billing address raises fraud probability, and a decision tree might provide a rule-like structure (e.g., “if IP country ≠ card country and amount > $1000 ⇒ flag fraud”). More complex models like XGBoost still allow some interpretability through feature importance scores, CHAP values, or partial dependence plots.

Classical ML models can be deployed in real-time with minimal latency. A logistic regression is essentially a dot-product of features, and even a large XGBoost ensemble can score a transaction in tens of milliseconds or less on modern hardware.

They also perform well with limited data. With careful feature engineering, a simple model can already catch a large fraction of fraud patterns. Consequently, industry adoption is widespread, many banks initially deploy logistic or tree-based models in production, and even today XGBoost is a common choice in fraud ML pipelines.

Weaknesses

A key limitation of classical ML models is the reliance on manual feature engineering. In other words, they cannot automatically invent new abstractions beyond the input features given. These models may miss complex patterns such as sequential spending behavior or R-ring collusion4 between groups of accounts unless analysts explicitly code such features (e.g., number of purchases in the last hour, or count of accounts sharing an email domain).

They may also struggle with high-dimensional data like raw event logs or image data (this is where deep learning excels). However, this is less an issue for structured transaction records.

Another challenge is class imbalance. The occurrence of fraud is typically rare (often $ <1\% $ of transactions), which can bias models to predict the majority “non-fraud” class. Techniques like balanced class weighting, undersampling, or SMOTE are often needed to train classical models effectively on imbalanced fraud data.5

Finally, while faster than deep neural networks, complex ensembles (hundreds of trees) can become memory-intensive and may require optimization for ultra-low latency at high transaction volumes.

Real-Time Suitability

Classical models are generally well-suited to real-time fraud scoring. They have low latency inference and modest resource requirements.

For example, a bank’s fraud engine might run a logistic regression and a few decision tree rules in under 10ms per transaction on a CPU. Even a sophisticated random forest or gradient boosting model can be served via highly optimized C++ libraries or cloud ML endpoints to meet sub-hundred-millisecond SLAs.6

The straightforward nature of these models also simplifies transaction monitoring and model updates. New data can be used to frequently retrain or update coefficients (even via online learning for logistic regression). The main caution is that if fraud patterns shift significantly (concept drift), purely static classical models will need frequent retraining to keep up.

In practice, many organizations retrain or fine-tune their fraud models on recent data weekly or even daily to adapt to new fraud tactics. So, while classical models are fast to deploy and iterate on, they do require ongoing maintenance to remain effective.

Examples

Representative research and use-cases for classical methods include:

- Logistic regression and decision trees as baseline models: Many banks have deployed logistic regression for real-time credit card fraud scoring due to its interpretability.

- Ensemble methods in academic studies: Research has focused on evaluating logistic vs. decision tree vs. random forest on a credit card dataset (often finding tree ensembles outperform linear models in Recall).7

- Kaggle competitions: XGBoost was heavily used in the Kaggle IEEE-CIS 2019 competition, leveraging high accuracy on tabular features.

- Hybrid systems: Many production systems combine manual business rules for known high-risk patterns with an ML model for subtler patterns, using the rules for immediate high-precision flags and the ML model for broad coverage.

Deep Learning Models

In recent years, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have been applied to transaction fraud detection with promising results. DNNs can automatically learn complex feature representations from raw data, potentially capturing patterns that are hard to manually engineer or find with classical ML models.

Deep Learning Architectures

Several deep architectures have been explored for fraud detection. Below, I summarize the most common types.

Feed-Forward Neural Networks (ANNs)

ANNs are multi-layer perceptron treating each transaction’s features as input neurons. These can model non-linear combinations of features beyond what logistic regression can capture. In practice, simple feed-forward networks have been used as a baseline deep model for fraud (e.g., a 3-layer network on credit card data). They often perform similarly to tree ensembles if ample data is available but are harder to interpret. They also don’t inherently handle sequential or time-based information beyond what the input features provide.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs are most famous for image-related tasks. However, they have also being been applied to fraud by treating transaction data as temporal or spatial sequences. For example, a CNN can slide over a sequence of past transactions for a user to detect local patterns or use 1D convolution on time-series of transaction amounts.

CNNs excel at automatic feature extraction of localized patterns. Some research reformats transaction histories into a 2D “image” (e.g., time vs. feature dimension) so that CNNs can detect anomalous shapes.

CNNs for detecting fraud have seen limited but growing use. One recent study reported ~99% detection accuracy with a CNN on a credit card dataset.8 However, such high accuracy is likely due to the highly imbalanced nature of the dataset (using AUC or F1 is more meaningful).

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

RNNs, including LSTM and GRU networks, are well-suited for sequential transactional data. They maintain a memory of past events, making them ideal for modeling an account’s behavior over time.

For example, an LSTM can consume a customer’s sequence of transactions (with timestamps) and detect if the latest transaction is anomalous given the recent pattern. This temporal modeling is very powerful for fraud because many fraud patterns only make sense in context (e.g., a sudden spending spike, or a purchase in a new country right after another far-away purchase).

Research has shown LSTM-based models can effectively distinguish fraudulent vs. legitimate sequences. In one case, an LSTM achieved significantly higher Recall than static models by catching subtle temporal shifts in user behavior.9 RNNs do require sequential data, so for one-off transactions without history they are less applicable (unless modeling at the merchant or account aggregate level).

Autoencoders

Autoencoders are unsupervised anomaly detection models that learn to compress and reconstruct data. When trained on predominantly legitimate transactions, an autoencoder captures the underlying structure of normal behavior (a.k.a. the “normal manifold”). As a result, it can reconstruct typical transactions with very low error, but struggles with atypical or anomalous ones. A transaction that doesn’t conform to the learned normal pattern will produce a higher reconstruction error. By setting a threshold, we can flag transactions with unusually high reconstruction error as potential fraud.

Autoencoders shine in fraud detection, particularly when labeled fraud data is scarce or nonexistent.10 Their strength lies in identifying transactions that deviate from the learned “normal” without requiring explicit fraud labels during training. For example, an autoencoder trained on millions of legitimate transactions will likely assign high reconstruction error to fraudulent ones it’s never seen before. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), which introduce probabilistic modeling and latent-space regularization—have also been explored for fraud detection, offering potentially richer representations of normal transaction behavior.11

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

GANs consist of a generator and discriminator. The generator creates synthetic data, while the discriminator tries to distinguish real from fake data.

There are two main applications of GANs in fraud detection:

Generate realistic synthetic fraud examples: GANs can augment training data to address class imbalance. The generator is trained to produce fake transactions that the discriminator (trained to distinguish real vs. fake) finds plausible. By adding these synthetic frauds to the training set, models (including non-deep models) can learn a broader decision boundary.

Serve as anomaly detectors: The generator tries to model the distribution of legitimate transactions, and the discriminator’s output can highlight outliers.

Some financial institutions have experimented with GANs. For example, Swedbank reportedly used GANs to generate additional fraudulent examples for training their models. However, GAN training can be complex and less common in production. Still, in research, GAN-based methods have shown improved Recall by expanding the fraud training sample space.12

Hybrid Deep Learning Models

There are also custom DNNs architectures combining elements of the above, or combining deep models with classical ones.

For example, a “wide and deep model” might have a linear (wide) component for memorizing known risk patterns and a neural network (deep) component for generalization. Another example is combining an LSTM for sequence modeling with a feed-forward network for static features (“dual-stream” models).

Ensembles of deep and non-deep models have also been used (e.g., using an autoencoder’s anomaly score as an input feature to a random forest). Recent research explores stacking deep models with tree models to improve robustness and interpretability.

Strengths

DNNs biggest advantage is automated feature learning. These types of models can uncover intricate, non-linear relationships and subtle correlations within massive datasets that older methods miss. They can digest raw inputs (inc. unstructured data) and find patterns without explicit human-designed features. For instance, an RNN can learn the notion of “rapid spending spree” or “geographical inconsistency” from raw sequences, which would be hard to capture with handcrafted features.

In fraud detection, large payment companies have millions of transactions which deep models can leverage to potentially exceed the accuracy of simpler models. DNNs also tend to improve with more data, whereas classical models may saturate in performance.

Another strength is handling complex data types. For example, if one incorporates additional signals like device fingerprints, text (e.g., product names), or network information, deep networks can combine these modalities more seamlessly (e.g., an embedding layer for device ID, an LSTM for text description, etc.).

In practice, DNNs have shown higher Recall at a given false-positive rate compared to classical models, in several cases.9 They are also adaptive architectures like RNNs or online learning frameworks can update as new data comes in, enabling continuous learning, which is important as fraud scenarios evolve.

Weaknesses

The primary downsides of DNN are complexity and interpretability.

Deep networks are considered “black boxes”, meaning that it’s non-trivial to explain why a certain transaction was flagged as fraudulent. This is problematic for financial institutions that need to justify decisions to customers or regulators. Techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) or Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) can help interpret feature importance for deep models, but it’s still harder compared to a linear model or decision tree.

Another issue is the data and compute requirement. Training large DNNs may require GPUs and extensive hyperparameter tuning, which can be overkill for some fraud datasets, especially if data is limited or highly imbalanced.13 In fact, many academic studies on the popular Kaggle credit card dataset (284,807 transactions) found that simpler models can match DNNs performance, likely because the dataset is small and mostly numeric features.

Overfitting is a risk too, fraud datasets are skewed and sometimes composed of static snapshots in time. A DNN might memorize past fraud patterns that fraudsters no longer use, if not carefully regularized.

Finally, latency can be a concern. A large CNN or LSTM might take longer to evaluate than a logistic regression. However, many deep models used for fraud are not excessively large (e.g., an LSTM with a few hundred units), and with optimized inference (batching, quantization, etc.) they can often still meet real-time requirements. I discuss latency more later, but suffice it to say that deploying deep models at scale might necessitate GPU acceleration or model optimizations in high-throughput environments.

Real-Time Suitability

DNNs models can be deployed for real-time fraud scoring, but it requires more care than classical models. Simpler networks (small MLPs) are no issue in real-time. However, RNNs or CNNs might introduce slight latency (tens of milliseconds). Nevertheless, modern inference servers and even FPGAs/TPUs can handle thousands of inferences per second. For instance, Visa reportedly targets fraud model evaluations in under ~25ms as part of their payment authorization pipeline. It’s feasible to achieve this with a moderately sized neural network and good infrastructure.

Scaling to high transaction volumes is another aspect. Deep models may consume more CPU/GPU resources, so a cloud deployment might need to autoscale instances or use GPU inference for peak loads.

A potential strategy for real-time use is a two-stage system: a fast classical model first filters obvious cases (either definitely legitimate or obviously fraudulent), and a slower deep model only analyzes the ambiguous middle chunk of transactions. This way, the heavy model is used on a fraction of traffic to keep overall throughput high.

Additionally, organizations often maintain a feedback loop. Flagged predictions are first reviewed by analysts or via outcomes like chargebacks, and then a DNN model is retrained frequently to incorporate the latest data.

Some deep models can be updated via online learning. For example, an RNN that continuously updates its hidden state or a streaming NN that periodically retrains on a rolling window of data, which helps keep them current with concept drift.

Examples

Notable examples of deep learning in fraud detection:

- Feedforward DNNs: PayPal in the mid-2010s applied neural networks to fraud, fintech companies like Feedzai have further advanced this methodology by combining DNNs with tree-based models.14

- RNNs and LSTMs: Multiple studies have shown that LSTM networks can detect sequential fraud behavior that static models miss, improving Recall by capturing temporal patterns. Large merchants have employed LSTM-based models to analyze user event streams, enabling the detection of account takeovers and session-based fraud in real-time.

- Autoencoder-based anomaly detection: Unsupervised autoencoders have been used by banks to flag new types of fraud. For instance, an autoencoder trained on normal mobile transactions flagged anomalies that turned out to be new fraud rings exploiting a loophole (detected via high reconstruction error).

- Hybrid models: Recent trends include using DNNs to generate features for a gradient boosted tree. One effective approach is to use deep learning models, such as autoencoders or embedding networks, to learn rich feature representations from transaction data. These learned embeddings are then fed into XGBoost, combining the deep models’ ability to capture complex patterns with the interpretability and efficiency of tree-based methods

Graph-Based Models

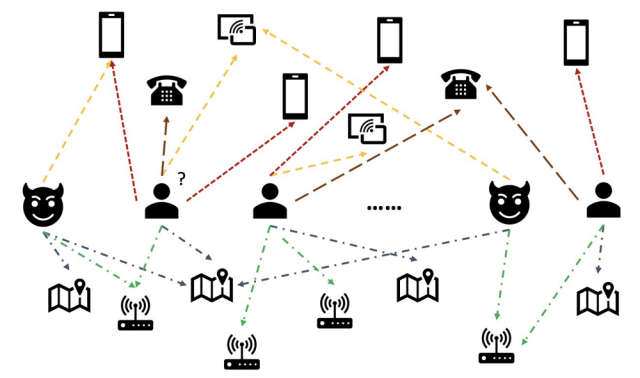

Groups of fraudsters might share information (e.g., using the same stolen cards or devices), or a single fraudster might operate many accounts that transact with each other. A powerful class of methods treats the financial system as a graph, linking entities like users, accounts, devices, IP addresses, merchants, etc. Graph-based fraud detection models aim to exploit these relational structures to detect fraud patterns that single-transaction models might miss. Classical graph algorithms can then be applied, such as community detection15 and link analysis (e.g., PageRank on the fraud graph).

For example, in a bipartite graph of credit card transactions, one set of nodes represent cardholders, another set are merchants, and there is an edge connecting a cardholder to a merchant for each transaction. Fraudulent cards might cluster via merchant edges (e.g., a fraud ring testing many stolen cards at one merchant), or vice versa.16 Similarly, for online payments we can create nodes for user accounts, email addresses, IP addresses, device IDs, etc., and connect nodes that are observed together in a transaction or account registration. This yields a rich heterogeneous graph of entities.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in recent years has led to many applications of this technology in fraud detection.17 18 19 GNNs are deep learning models designed for graph-structured data. They propagate information along edges, allowing each node to aggregate features from its neighbors. In fraud terms, a GNN can learn to identify suspicious nodes (e.g., users or transactions) by looking at their connected partners. For instance, if a particular device ID node connects to many user accounts that were later flagged as fraud, a GNN can learn to embed that device node as high-risk, which in turn raises the risk of any new account connected to it.

GNNs consider connections between accounts and transactions to reveal patterns of suspicious activity across the network. By incorporating relational context, GNNs have demonstrated higher fraud detection accuracy and fewer false positives than models that ignore graph structure. For example, combining GNNs features with an XGBoost classifier led to catching fraud that would otherwise go undetected and reducing false alarms due to the added network context. A GNN approach might catch a seemingly normal transaction if the card, device, or IP involved has connections to known frauds that a non-graph model wouldn’t see.

Several types of GNNs architectures have been used. Notably, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), GraphSAGE, heterogeneous GNNs for multi-type node graphs, and even Graph Transformers.

A popular benchmark for GNNs is the Elliptic dataset, a Bitcoin transaction graph where GNNs have been applied to identify illicit transactions by classifying nodes in a large transaction graph. GNNs have also been applied to credit card networks: e.g., researchers have built graphs linking credit card numbers, merchants, and phone numbers, and used a heterogeneous GNN to detect fraud cases involving synthetic identities and collusive merchants.20

Strengths

Graph-based methods can detect patterns of collusion and linkage that purely feature-based models miss. They effectively augment each transaction with context. Rather than evaluating an event in isolation, the model considers the broader network (device usage graph, money flow graph, etc.). This is crucial for catching fraud rings. For example, multiple accounts controlled by one entity or chains of transactions moving funds, which might appear normal individually but are anomalous in aggregate. GNNs in particular combine the best of both worlds: they leverage graph structure + attribute features together, learning meaningful representations of nodes/edges.20 This is important when fraudsters deliberately make individual transactions look innocuous but cannot hide the relationships (e.g., reusing the same phone or IP address across many accounts).

Another advantage is in reducing false positives by providing context. For example, a transaction with a new device might normally seem risky, but if that device has a long history with the same user and no links to bad accounts, a graph model can recognize it as low risk, avoiding a false alarm. Industry reports indicate that adding graph features or GNNs outputs has improved Precision of fraud systems by filtering out cases that looked suspicious in isolation but were safe in context.21

Weaknesses

The biggest challenge is complexity in implementation and deployment. Building and maintaining the graph data (a.k.a. the “graph pipeline”) is non-trivial. Transactions arrive in a stream and must update the graph in real-time (e.g., adding new nodes, new edges). Querying the graph for each new transaction’s neighborhood can be slow if not engineered well. The inference itself can be heavy. Running a GNNs means loading a subgraph and doing matrix operations that are costlier than a simple ML model. Consequently, many current GNNs solutions operate in batch mode (offline). There are limited reference architectures for real-time GNNs serving, though this is an active development area.

Another issue is scalability. Graphs of financial transactions or users can be enormous (millions of nodes, tens of millions of edges). Training a full GNNs on such a graph might not fit in memory or might be extremely slow without sampling techniques. Some approaches use graph sampling or partitioning to handle this, or only use GNNs to generate features offline.

GNNs can be hard to interpret (even more so than regular deep nets) since the features are aggregate of neighbors. It can be challenging to explain to an analyst why a certain account was flagged: the reason might be “it’s connected to three other accounts that had chargebacks,” which is somewhat understandable, but the GNN’s learned weights on those connections are not human-interpretable beyond that concept.

Real-Time Suitability

Real-time deployment of graph-based models is at the cutting edge. It is being done in industry but often with approximations. One pragmatic solution is to use graph analytics to create additional features for a traditional model. For example, compute features like “number of accounts sharing this card’s IP address that were fraud” or “average fraud score of neighbors” and update these in real-time, then let a gradient boosting model or neural network consume them. This doesn’t require full GNNs online inference, but captures some graph insights. However, truly deploying a GNNs in production for each event requires a fast graph database or in-memory graph store.

AWS demonstrated a prototype using Amazon Neptune (graph DB) + DGL (Deep Graph Library) to serve GNNs predictions in real-time by querying a subgraph around the target node for each inference.20 This kind of pipeline can risk score a transaction within seconds, which may be acceptable for certain use cases (e.g., online account opening fraud). However, for high-frequency card transactions that need sub-second decisions, a full GNNs might still be too slow today unless heavily optimized.

An alternative is what Nvidia suggests: use GNNs offline to produce node embeddings or risk scores, then feed those into a superfast inference system (like an XGBoost model or a rules engine) for the real-time decision.21 This hybrid approach was shown to work at large scale, where GNN-based features improved detection by even a small percent (say 1% AUC gain), which for big banks translates to millions saved.

Lastly, maintaining graph models demands continuous updates as the graph evolves. This is still manageable, as new data can be incrementally added, but one must watch for concept drift in graph structure. For example, fraud rings forming new connectivity patterns.

Examples

Representative examples of graph-based fraud detection:

- Blockchain networks: The Elliptic Bitcoin Dataset is a graph of 203,769 transactions (nodes) with known illicit vs. licit labels. GNNs models on this dataset achieved strong results, showing that analyzing the transaction network is effective for detecting illicit cryptocurrency flows.

- Credit card networks: Researchers built a graph of credit card transaction and applied a GNNs which outperformed a baseline MLP by leveraging connections (e.g., card linked to a fraudulent merchant gives card a higher fraud probability).

- E-commerce networks: Companies like Alibaba and PayPal have internal systems modeling user networks. For example, accounts connected via a shared device or IP can indicate sybil attacks or mule accounts. Graph algorithms identified clusters of accounts that share many attributes (forming fraud communities) which were then taken down as a whole.

- Telecom identity fraud: Graphs connecting phone numbers, IDs, and addresses have been used to catch identity fraud rings. A famous case is detecting “bust-out fraud” in which a group of credit card accounts all max out and default: the accounts often share phone or address; linking them in a graph helps catch the ring before the bust-out completes.

- Social networks: In social finance platforms or peer-to-peer payments, graph methods are used to detect money laundering or collusion by analyzing the network of transactions among users (e.g., unusually interconnected payment groups).

Overall, graph-based methods, especially GNNs, represent a cutting-edge approach that can significantly enhance fraud detection by considering relational data. As tooling and infrastructure improve (graph databases, streaming graph processing), I expect to see more real-time GNNs deployments for fraud in the coming years.

Transformer Models

Transformers

Transformers (originally developed for language processing) have revolutionized many domains, and they are now making inroads in fraud detection. The key innovation of transformers is the self-attention mechanism, which allows modeling long-range dependencies in sequences. In the context of transaction data, transformers can analyze transaction sequences or sets of features in flexible ways.

Large pre-trained foundation models (akin to GPT or BERT, but for payments) are emerging. In this case, a model is pre-trained on massive amounts of transaction data to learn general patterns, then fine-tuned for specific fraud tasks. So that these models can “speak” transactional data.

“One of the most notable recent developments comes from Stripe’s transformer-based payments foundation model. This is a large-scale self-supervised model trained on tens of billions of transactions to create embeddings of each transaction. The idea is analogous to how LLMs work: to learn a high-dimensional embedding for a transaction that captures its essential characteristics and context. Transactions with similar patterns end up with similar embeddings, e.g., transactions from the same bank or the same email domain cluster together in embedding space. These embeddings serve as a universal representation that can be used for various tasks: fraud detection, risk scoring, identifying businesses in trouble, etc. For the fraud use-case, Stripe reports a dramatic improvement: by feeding sequences of these transaction embeddings into a downstream classifier, they achieved an increase in detection rate for certain fraud attacks from 59% to 97% overnight. In particular, they targeted “card testing fraud” (i.e., fraudsters testing stolen card credentials with small purchases), something that often hides in high-volume data. The transformer foundation model was able to spot subtle sequential patterns of card testing that previous feature-engineered models missed, blocking attacks in real-time before they could do damage.”

Researchers have applied Transformer encoders to tabular data as well.22 For example, using models like TabTransformer or integration of transformers with structured data. They reported improved accuracy over MLPs and even over tree models in some cases.23

The ability of transformers to focus attention on important features or interactions could be beneficial for high-dimensional transaction data.

For example, a transformer might learn to put high attention on the device_id feature when the ip_address_country is different from the billing country, effectively learning a rule-like interaction that would be hard for a linear model.

Transformers can also model cross-item sequences: one can feed a sequence of past transactions as a “sentence” into a transformer, where each transaction is like a token embedding (comprising attributes like amount, merchant category, etc.). The transformer can then output a representation of the sequence or of the next transaction’s risk. This is similar to an RNN’s use but with the advantage of attention capturing long-range dependencies (e.g., a pattern that repeats after 20 transactions). There have been experiments where a transformer outperformed LSTM on fraud sequence classification, due to its parallel processing and ability to consider all transactions’ relations at once.

Another angle is using transformer models for entity resolution and representation in fraud. For instance, a transformer can be trained on the corpus of all descriptions or merchant names that a user has transacted with, thereby learning a “profile” of the user’s spending habits and detecting an out-of-profile transaction (similar to how language models detect an odd word in a sentence). Additionally, BERT-like models can be used on event logs or customer support chats to detect social engineering fraud attempts, though that’s adjacent to transaction fraud.

Foundation models

Foundation models in fraud detection refer to large models trained on broad data that can then be adapted. Besides Stripe’s payments’ model, other financial institutions are likely developing similar pre-trained embeddings. For example, a consortium of banks could train a model on pooled transaction data (in a privacy-preserving way, or via federated learning) to get universal fraud features.

These large models may use transformers or other architectures, but the common theme is self-supervised learning: e.g., predicting a masked field of a transaction (merchant_category, or amount) from other fields, or predicting the next transaction given past ones.

Through such tasks, the model gains a deep understanding of normal transactional patterns.

When fine-tuned on a specific fraud dataset, it starts with a rich feature space and thus performs better with less training data than a model from scratch.

This is analogous to how image models pre-trained on ImageNet are fine-tuned for medical images with small datasets.

Strengths

Transformers and foundation models bring state-of-the-art pattern recognition to fraud. They particularly shine in capturing complex interactions and sequential/temporal patterns. The attention mechanism allows the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input for each decision. For fraud, this could mean focusing on certain past transactions or specific features that are indicative of risk in context. This yields high detection performance, especially for “hard fraud” that evades simpler models.

Another strength is multitasking capabilities. A large foundation model can be trained once and then used for various related tasks such as fraud, credit risk, or marketing predictions simply by fine-tuning or prompting, rather than maintaining separate models for each. This “one model, many tasks” approach can simplify the system and leverage cross-task learning (e.g., learning what a risky transaction looks like might also help predict chargebacks or customer churn).

Moreover, transformers can handle heterogeneous data relatively easily. One can concatenate different feature types and the self-attention will figure out which parts to emphasize. For example, Stripe’s model encodes each transaction as a dense vector capturing numeric fields, categorical fields, etc., all in one embedding.

Finally, foundation models can enable few-shot or zero-shot fraud detection. Imagine detecting a new fraud pattern that wasn’t in the training data. A pre-trained model that has generally learned “how transactions usually look” might pick up the anomaly better than a model trained only on past known frauds.

Weaknesses

The obvious downsides are resource intensity and complexity. Training a transformer on billions of transactions is a monumental effort, requiring distributed training, specialized hardware (TPUs/GPUs), and careful tuning. This is typically only within reach of large organizations or collaborations. In production, serving a large transformer in real-time can be challenging due to model size and latency. Transformers can have millions of parameters, and even if each inference is 50-100ms on a GPU, at very high transaction volumes (thousands per second) this could be costly or slow without scaling out. Techniques like model quantization, knowledge distillation, or efficient transformer variants (e.g., Transformer Lite) might be needed.

Another concern is explainability. Even more so than a standard deep network, a giant foundation model is a black box. Understanding its decisions requires advanced explainable AI methods, like interpreting attention weights or using SHAP on the embedding features, which is an active research area. For regulated industries, one might still use a simpler surrogate model to justify decisions externally, while the transformer works under the hood.

Overfitting and concept drift are also concerns. A foundation model might capture a lot of patterns, including some that are spurious or not causally related to fraud. If fraudsters adapt, the model might need periodic re-training or fine-tuning with fresh data to unlearn outdated correlations. For example, the Stripe model is self-supervised (no fraud labels in pre-training) which helps it generalize, but any discriminative fine-tuning on fraud labels will still need updating as fraud evolves.

Real-Time Suitability

Surprisingly, with the right engineering, even large transformers can be used in or near real-time. For example, optimizing the embedding generation via GPU inference or caching mechanisms. One strategy is to pre-compute embeddings for entities (like a card or user) so that only incremental computation is needed per new transaction. Another strategy is two-stage scoring: use a smaller model to thin out events, then apply the heavy model to the most suspicious subset. If real-time means sub-second (say <500ms), a moderately sized transformer model on modern inference servers can fit that window, especially if batch processing a few transactions together to amortize overhead. Cloud providers also offer accelerated inference endpoints (like AWS Inferentia chips or Azure’s ONNX runtime with GPU) to deploy large models with low latency.

That said, not every company will want to deploy a 100M+ parameter model for each transaction if a simpler model would do. There is a trade-off between maximum accuracy and infrastructure cost/complexity. In many cases, a foundation model could be used to periodically score accounts offline (to detect emerging fraud rings) and a simpler online model handle immediate decisions, combining their outputs.

Examples

Use cases and research for transformers in fraud:

- Stripe’s Payments Foundation Model: A transformer-based model trained on billions of transactions, now used to embed transactions and feed into Stripe’s real-time fraud systems. It improved certain fraud detection rates from 59% to 97% and enabled detection of subtle sequential fraud patterns that were previously missed.

- Tabular transformers: Studies like Chang et al.22 applied a transformer to the Kaggle credit card dataset and compared it to SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost, etc. The transformer achieved comparable or superior Precision/Recall, demonstrating that even on tabular data a transformer can learn effectively.

- Sequence anomaly detection: Some works use transformers to model time series of transactions per account. A transformer may be trained to predict the next transaction features; if the actual next transaction diverges significantly, it could flag an anomaly. This is analogous to language model use (predict next word).

- Cross-entity sequence modeling: Transformers can also encode sequences of transactions across entities, e.g., tracing a chain of transactions through intermediary accounts (useful in money laundering detection). The recent FraudGT model24 combines ideas of GNNs and transformer to handle transaction graphs with sequential relations.

- Foundation models for documents and text in fraud: While not the focus here, note that transformers (BERT, GPT) are heavily used to detect fraud in textual data (e.g., scam emails, fraudulent insurance claims text, etc). In a holistic fraud system, a foundation model might take into account not just the structured transaction info but also any unstructured data, like customer input or messages, to make a decision.

Transformer-based models and foundation models represent the frontier of fraud detection modeling. They offer unparalleled modeling capacity and flexibility, at the cost of high complexity. Early results, especially from industry leaders, indicate they can substantially raise the bar on fraud detection performance when deployed thoughtfully. As these models become more accessible (with open-source frameworks and possibly smaller specialized versions), more fraud teams will likely adopt them, particularly for large-scale, multi-faceted fraud problems where simpler models hit a ceiling.

Appendix

Public Datasets

Research in fraud detection often relies on a few key public datasets to evaluate models, given that real financial data is usually proprietary.

Below I summarize some of the most commonly used datasets, along with their characteristics:

Credit Card Fraud Detection (Kaggle, 2013): A classic dataset containing real European credit card transactions over two days. Its key characteristics are its extreme class imbalance (0.172% fraud) and anonymized features (28 PCA components), making it a standard benchmark for testing algorithms on imbalanced data.

Credit Card Fraud Detection (Kaggle, 2013): A classic dataset containing real European credit card transactions over two days. Its key characteristics are its extreme class imbalance (0.172% fraud) and anonymized features (28 PCA components), making it a standard benchmark for testing algorithms on imbalanced data. IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection (Kaggle, 2019): A large, rich dataset from an e-commerce provider, released for a Kaggle competition. It features ~300 raw features (device info, card details, etc.), missing values, and a moderate imbalance (3.5% fraud). It is ideal for evaluating complex feature engineering and ensemble models for card-not-present fraud.

IEEE-CIS Fraud Detection (Kaggle, 2019): A large, rich dataset from an e-commerce provider, released for a Kaggle competition. It features ~300 raw features (device info, card details, etc.), missing values, and a moderate imbalance (3.5% fraud). It is ideal for evaluating complex feature engineering and ensemble models for card-not-present fraud. PaySim (Kaggle, 2016): A large-scale synthetic dataset that simulates mobile money transactions. It contains over 6 million transactions and is useful for testing model scalability in a controlled environment. Because it is synthetic, models may achieve unrealistically high performance.

PaySim (Kaggle, 2016): A large-scale synthetic dataset that simulates mobile money transactions. It contains over 6 million transactions and is useful for testing model scalability in a controlled environment. Because it is synthetic, models may achieve unrealistically high performance. Elliptic Bitcoin Dataset (Kaggle, 2019): A temporal graph of over 200,000 Bitcoin transactions, where nodes are transactions and edges represent fund flows. It is a key benchmark for evaluating graph-based fraud detection methods like GNNs. Only a small fraction of nodes are labeled as illicit, presenting a challenge.

Elliptic Bitcoin Dataset (Kaggle, 2019): A temporal graph of over 200,000 Bitcoin transactions, where nodes are transactions and edges represent fund flows. It is a key benchmark for evaluating graph-based fraud detection methods like GNNs. Only a small fraction of nodes are labeled as illicit, presenting a challenge.

⚠️ Due to high imbalance, accuracy is not informative (e.g., the credit card dataset has 99.8% non-fraud, so a trivial model gets 99.8% accuracy by predicting all non-fraud!). Hence, papers report metrics like AUC-ROC, Precision/Recall, or F1-score. For instance, on the Kaggle credit card data, an AUC-ROC around 0.95+ is achievable by top models, and PR AUC is much lower (since base fraud rate is 0.172%). In IEEE-CIS data, top models achieved about 0.92–0.94 AUC-ROC in the competition. PaySim being synthetic often yields extremely high AUC (sometimes >0.99 for simple models) since patterns might be easier to learn. When evaluating on these sets, it’s crucial to use proper cross-validation or the given train/test splits to avoid overfitting (particularly an issue with the small Kaggle credit card data).

Overall, these datasets have driven a lot of research. However, one should be cautious when extrapolating results from them to real-world performance. Real production data can be more complex (concept drift, additional features, feedback loops). Nonetheless, the above datasets provide valuable benchmarks to compare algorithms under controlled conditions.

External Resources

- Awesome Graph Fraud Detection Papers

- DGFraud: A Deep Graph-based Toolbox for Fraud Detection

- FraudGT: A Simple, Effective, and Efficient Graph Transformer for Financial Fraud Detection

Footnotes

Oztas, Berkan, et al. “Transaction monitoring in anti-money laundering: A qualitative analysis and points of view from industry.” Future Generation Computer Systems (2024). ↩

G. Praspaliauskas, V. Raman (2023). “Real-time fraud detection using AWS serverless and machine learning services. AWS Machine Learning Blog – outlines a serverless architecture using Amazon Kinesis, Lambda, and Amazon Fraud Detector for near-real-time fraud prevention.” ↩

Desai, Ajit, Anneke Kosse, and Jacob Sharples. “Finding a needle in a haystack: a machine learning framework for anomaly detection in payment systems..” The Journal of Finance and Data Science 11 (2025): 100163. ↩

R-ring collusion is a form of coordinated behavior where multiple accounts, potentially belonging to different individuals or groups, engage in fraudulent activities that benefit each other. ↩

For a Python library dedicated to handling imbalanced datasets and techniques, see imbalanced-learn, which provides tools for oversampling, undersampling, and more. ↩

Service Level Agreement (SLA) is a commitment between a service provider and a client that outlines the expected level of service, including performance metrics and response times. ↩

Afriyie, Jonathan Kwaku, et al. “A supervised machine learning algorithm for detecting and predicting fraud in credit card transactions. Decision Analytics Journal 6 (2023): 100163.” ↩

Onyeoma, Chidinma Faith, et al. “Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Deep Neural Network with Shapley Additive Explanations.” 2024 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT). IEEE, 2024. ↩

Kandi, Kianeh, and Antonio García-Dopico. “Enhancing Performance of Credit Card Model by Utilizing LSTM Networks and XGBoost Algorithms.” Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 7.1 (2025): 20. ↩ ↩2

Cherif, Asma, et al. “Encoder–decoder graph neural network for credit card fraud detection.” Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 36.3 (2024). ↩

Alshameri, Faleh, and Ran Xia. “An Evaluation of Variational Autoencoder in Credit Card Anomaly Detection.” Big Data Mining and Analytics (2024). ↩

Charitou, Charitos, Artur d’Avila Garcez, and Simo Dragicevic. “Semi-supervised GANs for fraud detection.” 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2020. ↩

Huang, Huajie, et al. “Imbalanced credit card fraud detection data: A solution based on hybrid neural network and clustering-based undersampling technique.” Applied Soft Computing 154 (2024). ↩

Branco, Bernardo, et al. “Interleaved sequence RNNs for fraud detection.” Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining. 2020. ↩

Masihullah, Shaik, et al. “Identifying fraud rings using domain aware weighted community detection.” International Cross-Domain Conference for Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022. ↩

Boyapati, Mallika, and Ramazan Aygun. “BalancerGNN: Balancer Graph Neural Networks for imbalanced datasets: A case study on fraud detection..” Neural Networks 182 (2025): 106926. ↩

Motie, Soroor, and Bijan Raahemi. “Financial fraud detection using graph neural networks: A systematic review.” Expert Systems with Applications (2024). ↩

Shih, Yi-Cheng, et al. “Fund transfer fraud detection: Analyzing irregular transactions and customer relationships with self-attention and graph neural networks.” Expert Systems with Applications. 2025. ↩

Tong, Guoxiang, and Jieyu Shen. “Financial transaction fraud detector based on imbalance learning and graph neural network.” Applied Soft Computing 149 (2023): 110984. ↩

Jian Zhang et al. (2022). “Build a GNN-based real-time fraud detection solution using Amazon SageMaker, Amazon Neptune, and DGL. AWS ML Blog – explains how graph neural networks can be served in real-time for fraud detection, noting challenges in moving from batch to real-time GNN inference.” ↩ ↩2 ↩3

Summer Liu et al. (2024). “Supercharging Fraud Detection in Financial Services with GNNs. NVIDIA Technical Blog.” ↩ ↩2

Yu, Chang, et al. “Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Advanced Transformer Model.” 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking, and Applications (MetaCom). IEEE, 2024. ↩ ↩2

Krutikov, Sergei, et al. “Challenging Gradient Boosted Decision Trees with Tabular Transformers for Fraud Detection at Booking.com.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.13692 (2024). ↩

Lin, Junhong, et al. “FraudGT: A Simple, Effective, and Efficient Graph Transformer for Financial Fraud Detection.” Proceedings of the 5th ACM International Conference on AI in Finance. 2024. ↩